The Landscape of Independent Film and Political Media

For the last three years, 1919 has had the opportunity to attend the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), one of the most renowned film festivals in the world. While TIFF has grown to become one of the world's largest and most successful film festivals, occasionally it becomes a platform for politically driven films. The 2024 festival’s selection of films such as No Other Land and Sudan, Remember Us, underscore a central contradiction within the independent film industry. What happens when an institution dedicated to commercial success begins to engage with, or capitalize on, politically driven stories? These selections raise intriguing questions about TIFF's role: Can it amplify critical messaging while balancing the boundaries of commercial appeal and social impact, all while maintaining an apolitical, neoliberal stance that keeps corporate sponsors satisfied?

“

What happens when an institution dedicated to commercial success begins to engage with, or capitalize on, politically driven stories?”

In contrast, the art and media produced by 1919 is primarily concerned with the political nature of our world and how our cultural products; films, music, literature media, etc., may be used as a form of deterrence against our political foes and the systems they threaten and violate us with. While we did not hold an international film festival in September, we did organize a community film screening of The Spook Who Sat By The Door for our Calgary chapter. Following its 1973 release, The Spook was condemned for inciting dangerous anti-American propaganda promoting domestic revolt and violence against the U.S. government. The Spook film exemplifies the powerful threat political films can pose to art, film, and government institutions at large and the full extent to which these institutions will go to suppress their reach.

In discussing these three films, the contents of them, and the contexts in which they were shown, we want to examine and critically understand the journey and the contradictions that exist within the distribution of political media then and now. What is the function of a political story told for a large commercial audience versus an intimate community audience? What does a platform like TIFF, a commercial powerhouse and marker of major industry success, have to gain from screening films that delve into ongoing geopolitical conflicts? What are the implications for political movements when a festival of this scale platforms stories rooted in anti-colonial struggle and resistance?

No Other Land (2024) documents the Palestinian struggle in Masafer Yatta and offers a raw portrayal of activists’ defiance against Israeli Defense Forces’ attempts to displace them. Through a mixture of intimate moments, the film captures the community's rebuilding efforts during the night as a symbol of quiet resistance against overwhelming odds. Yet, despite its timely significance and mass relevance, the film remains difficult to access outside of the festival circuit, a common issue for all independent films, not just stories that are politically driven.

No Other Land (2024)

Sudan, Remember Us (2024), directed by Hind Meddeb, recounts the post-revolution journey of Sudanese youth fighting for a democratic government after the fall of Omar al-Bashir. The film was praised for its emotional depth and focus on the resilience of activists, but like No Other Land, it faces distribution challenges.

Sudan, Remember Us (2024)

Independent films, especially those addressing political events, face unique challenges in breaking through to mainstream distribution and reaching diverse audiences. Unlike major studio productions, which often benefit from substantial financial backing and established distribution channels, independent filmmakers work within a constrained system that limits both visibility and access.

Independent films are typically funded through a mix of grants, donations, and limited sponsorships (often from organizations aligned with their themes). While this funding model offers some creative freedom, it also creates financial barriers, particularly for films that tackle political topics. These barriers affect not only production, but the resources available for promotion, distribution, and marketing; making it difficult for these films to reach audiences beyond niche circles.

In our current socio-political climate, films like No Other Land and Sudan, Remember Us, are typically relegated to indie festivals like Images, Inside Out, and the Toronto Palestine Film Festival, and if they're lucky, they may crack TIFF and other major commercial festivals. The question of these films reaching mainstream platforms beyond TIFF, such as Netflix and Cineplex, almost seems like an unnatural question amidst the backdrop of today's commercial expectations and prevailing neoliberal thought.

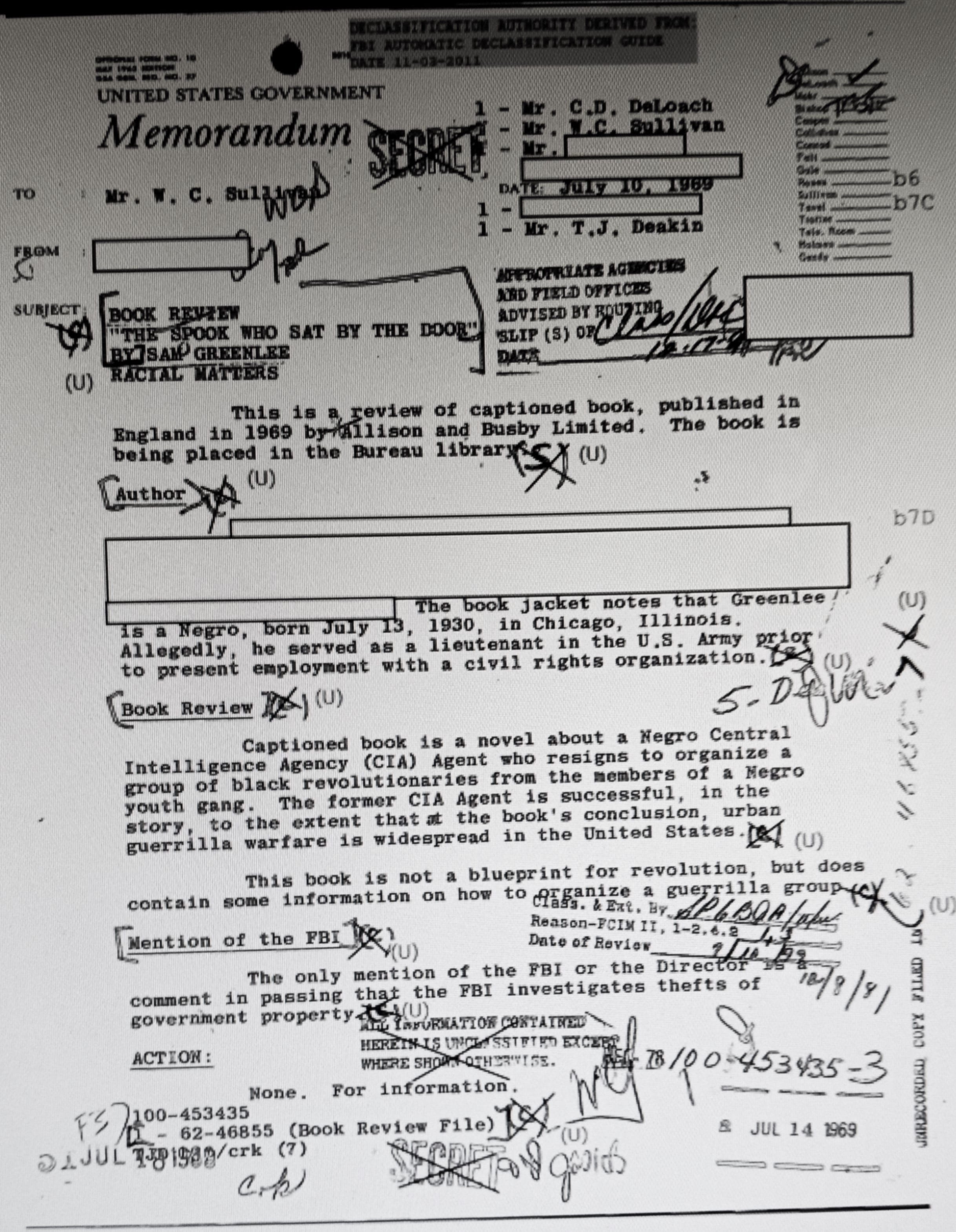

The censorship and suppression of The Spook shortly after its 1973 release exemplifies the threat political films can and should pose to art, film, and government institutions at large. The film, directed by Ivan Dixon, tells the story of Dan Freeman, a Black CIA agent who becomes disillusioned with the tokenism and racism of the agency. Freeman takes his CIA training back to his community, organizing young Black men into a guerrilla resistance unit aimed at overthrowing the oppressive U.S. government.

The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973)

Emerging during a period of intense civil rights activism and widespread social unrest in the United States, the film was quickly pulled from theatres under pressure from government agencies alarmed by its portrayal of Black militancy and organized resistance. Amidst the political climate of the early 1970s, federal agencies like the FBI were actively working to dismantle Black liberation movements through counterintelligence programs like COINTELPRO. Following The Spooks' initial pull from theatres, it would be another 30 years until Dixon’s personal print was used for a DVD release and the film would regain popularity.

1969 FBI document in regards to Sam Greenlee’s original novel, The Spook Who Sat By The Door.

While all three of these films emphasize resilience and organized resistance against oppressive government regimes, the distinction between overt revolution and militancy in The Spook compared to non-violent forms of resistance in No Other Land and Sudan, Remember Us, is quite stark.

Documentaries, by definition, document a historical record or present reality. Beyond that, documentaries can also induce sympathy as they capture current events and real-world issues that viewers may already recognize from mainstream media platforms. This framing often allows documentaries to highlight injustice while positioning them as reflections on the human condition rather than incitements to action.

Films like No Other Land and Sudan, Remember Us document real struggles against oppressive regimes and are framed around factual present day events—such as the Palestinian resistance to Israeli forces in the West Bank, and the youth-led push for democratic reforms in Sudan. Because these documentaries are capturing current events or recounting past struggles, they are legitimized and acclaimed for capturing truths and not necessarily for making a critique of the actual conditions the Palestinian and Sudanese peoples are experiencing. These documentaries are seen as chronicling an unfortunate, seemingly distant reality—one lacking a clear, accountable agent.

Contrastingly, fictional narratives, particularly those that imagine successful resistance such as The Spook, present a different kind of challenge. They not only propose that resistance is necessary, but that it can succeed—and that belief, that seed, can bear fruit much more dangerous to institutions and governments than the funding and documenting of the very suffering they cause.

“They not only propose that resistance is necessary, but that it can succeed—and that belief, that seed, can bear fruit much more dangerous to institutions and governments than the funding and documenting of the very suffering they cause.”

A film like The Spook—with its bold narrative of overthrowing government systems—would likely face immense challenges in today’s film landscape, where corporate sponsorship and neoliberal imaginations dictate which political struggles should be platformed in commercial spaces. A film like this would have a hard time making it from manuscript to production in 1973, 2024, 1995, or any year for that matter.

The Spook Who Sat By The Door (1973)

The days of DVD releases and the Black Power Movement that characterized the political climate at the time of The Spooks’ release are behind us. However, as of recent, The Spook was added to the National Film Registry in 2012 and received a 4K restoration from the Library of Congress and Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, which has seen the film run at independent film festivals such as the New York Film Festival (NYFF) and the Brooklyn Academy of Music Film Festival (BAM).

The Spooks resurgence in our current political moment can be partly related to the nostalgic effect of restoring a historical Black cultural artifact but also related to its relevance in today's political climate. The call for domestic revolution and Black militancy today feels novel amidst the widespread political apathy, neutrality, and pacification that encapsulates the current capture of the western left.

The Spook Who Sat By the Door (1973)

Determining whether or not the threat of Black militancy and domestic revolution being invoked today is truly a fear of the colonial establishment is an interesting thought experiment but not within the scope of this piece. Nonetheless, if a film today were to explore themes as bold as, say, a resistance force dismantling NATO and calling for the fall of the US empire, the reception would likely echo the fears that surrounded The Spook at its time. Censorship would not be necessary as the current political climate in 2024 would hardly allow such a story to reach community and indie screens— let alone mainstream outlets.

Reflecting on the discussion of the contents and contexts of these three films, it is clear that both then and now, the establishment exercises a supreme grip over the development of political art and media that is commercially platformed and produced.

The journey of politically driven independent films reveals the tension between bold storytelling and the systemic constraints of the industry. Films like No Other Land and Sudan, Remember Us use a documentary-style approach to capture real struggles, confronting institutional power in ways that are urgent yet observational. In contrast, a film like The Spook, with its fictional narrative inspiring direct resistance, induced fear into the US government and demonstrates how stories that envision successful defiance can provoke heightened scrutiny. This dynamic highlights that certain political narratives are allowed to be seen, while others are suppressed—not just because of what they depict, but because of what they inspire.

Documentaries may face challenges in gaining wide distribution, but their focus on real events offers them a form of artistic protection. Fictional films that idealize or envision achievable resistance face greater barriers as they challenge audiences to see revolution not as a distant or doomed concept, but as a practical and reasonable response to their political and material conditions. This difference is central to understanding how political content is managed, censored, or platformed in the world of independent cinema and media. By bringing marginalized perspectives and visions of change to audiences through community screenings and grassroots efforts, independent film keep revolutionary narratives alive, challenges hegemonic efforts at manufacturing consent, and offers vital engagement with global struggles that would otherwise go unseen.